The Chicago Manual of Style

Table of Contents

There is no universally accepted format for formatting and documenting citations in academic writing. Different disciplines, and even different journals within a discipline, are each likely to have their own partly rational and partly idiosyncratic customs and rules. An important part of scholarly training is learning what the rules are in one’s particular field, so one can display the right kind of learning and professionalization.

In history and the humanities, Chicago style is a widely-used format, favored by those who prefer the traditional look of footnotes (or endnotes) rather than in-text citations.

Chicago document formats

Paper and binding Use sturdy white, unlined 8.5″ by 11″ paper. Chicago style is to use paperclips (in the upper left corner) rather than staples, though some teachers may have their own requirements. Don’t use binders or plastic covers unless your teacher wants them. Don’t hold your paper together by folding or tearing pages.

Emphasis

For titles and emphasis of books, use either underlining or italics. Choose one and be consistent.

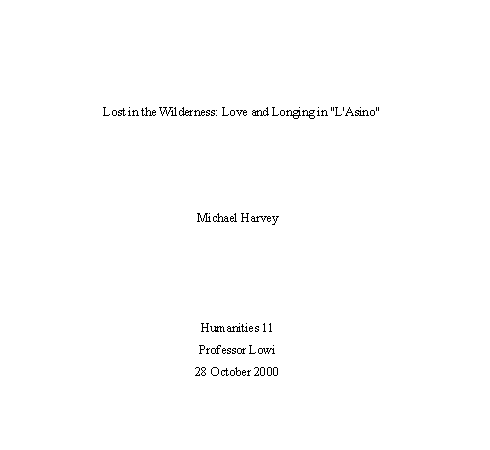

Title page

Papers longer than five pages need a separate title page. It looks something like this:

The title is centered, about half-way down the page. If it exceeds a single line, break it at a natural point.

The essay begins on the next page with no special heading:

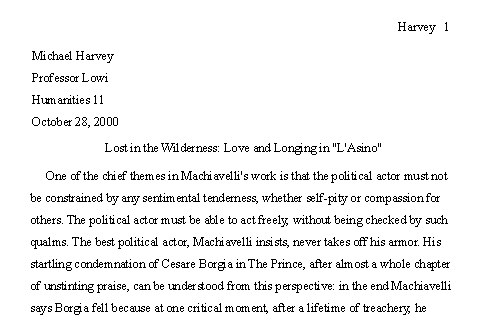

Short paper (no separate title page)

Short essay papers (no more than five pages) don’t need a separate title unless a writers requires one. Here’s an example of the first page of a short paper, Chicago-style. Note that with no title page, the first page includes information on the student, course, professor, and date (different teachers may modify this).

Notes (endnotes or footnotes)

Chicago style uses bibliographic notes rather than in-text citations. Your teacher will require to use either footnotes (at the foot of the page) or endnotes (at the end of the essay). Detailed treatment of notes for different kinds of texts follows below, but here are the general formats.

Authors’ names are not inverted in notes (Michael Harvey, not Harvey, Michael). See below for examples.

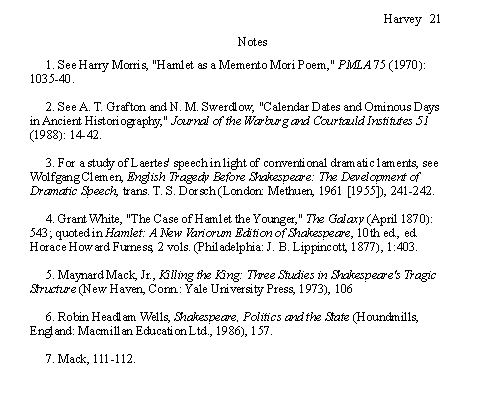

Endnotes

Endnotes are gathered together at the end of the essay, commencing on a new page. Pagination continues from the essay. The word Notes is centered on the first line (subsequent pages of notes don’t have a title). Notes are numbered, following the note numbers used in the text. In the endnotes the numbers are in normal text (not superscript), and are followed by a period and a space. The first line of the note is indented a half-inch (or five spaces); subsequent lines are flush left. Notes are single-spaced, with a blank line between notes.

Footnotes

Footnotes occur at the bottom of each page. A line extending about 40 spaces or a bit less than half the width of the page separates the notes from regular text. Notes are numbered; the numbers are in normal text (not superscript), and are followed by a period and a space. The first line of the note is indented a half-inch (or five spaces);: subsequent lines are flush left. Notes are single-spaced, with a blank line between notes.

Basic Chicago citation style

The traditional Chicago citation style consists of references in notes, either footnotes or endnotes (footnotes go at the bottom of the page on which the note occurs, and endnotes are gathered together at the end of the paper; which you use depends on what your teacher prefers). The examples here assume footnotes, but endnotes would look the same.

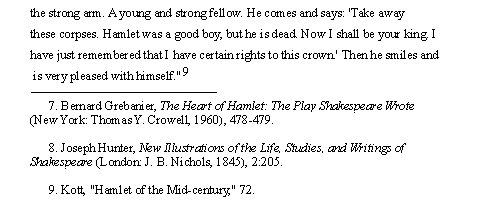

The first citation of a work requires full bibliographic information. Subsequent citations take a brief note: usually just author and page. At the end of the paper is a bibliography with a complete, alphabetized list of all works cited. The point of Chicago style is to make it easy for readers to see at a glance the source of a citation.

|

The quoted passage The novel opens evocatively, with a beginning that sounds almost like an ending: “So the beginning of this was a woman and she had come back from burying the dead.” The footnote (assuming this is the first citation from this text) 11. Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 9. The footnote (assuming this is not the first citation from this text) 11. Hurston, 9. |

Note that the page number is given without any abbreviation like p.

Introducing quotations elegantly takes some practice. Check Effective quoting for help.

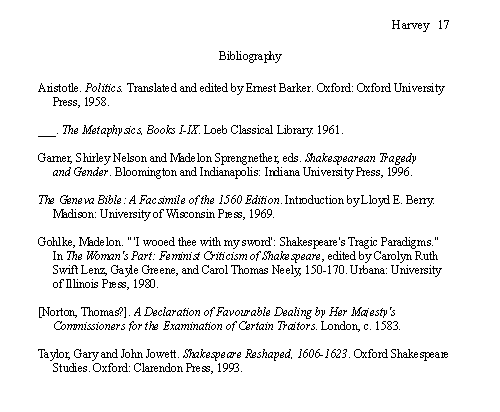

Bibliography

Chicago style requires you to list your sources with full bibliographic information at the end of the paper (after any endnotes). The usual title is “Bibliography,” though other titles (like Works Cited or References) are permitted. The bibliography begins on a new page and continues the paper’s page numbers. Like other page numbers, the page number appears in the upper-right hand corner, half an inch from the top and flush with the right margin (all margins are one inch).

Chicago notes and bibliography details

WriteMyEssay.nyc helps with many questions about Chicago notes and bibliographic entries. But before we launch into the minutiae of how to cite this or that source, let’s state a couple of guiding principles: the point of Chicago style, or indeed any citation style, is not rules for their own sake, but as conventions meant to enhance clarity, readability, and usefulness. If any of the rules below seem to produce unclear citations or a difficult-to-read paper, that may because this summary treatment makes Chicago style seem more rigid than it really is. If you want further guidance, consult the 900-page Manual itself, or send a query to the Chicago Manual FAQ. Each entry below shows how to format the footnote citation and the bibliographic entry, and provides examples when needed. For full details and hundreds of special cases, consult the Chicago Manual of Style. Here are the types of sources detailed below (the next section treats Internet sources):

1. Basic book format Footnote/endnote

| First footnote 1. David Daiches, Moses: The Man and his Vision (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1975).

Subsequent footnotes 3. Daiches, 176. |

Bibliographic entry

| Daiches, David. Moses: The Man and his Vision. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1975. |

2. Basic journal article format

Footnote/endnote

| First footnote 2. Julia Reinhard Lupton, “Creature Caliban,” Shakespeare Quarterly 51.1 (2000): 17.

Subsequent footnotes 3. Lupton, 19. |

Bibliographic entry

| Lupton, Julia Reinhard. “Creature Caliban.” Shakespeare Quarterly 51.1 (2000): 1-23. |

3. Two or more works by the same author

Footnote/endnote

Citing more than work by a scholar is no problem for the first citation, because the first note will have full bibliographic information. But subsequent citations will have to identify not only the scholar, but also the specific work, as this example shows:

|

Levin amplifies his argument in a rebuttal to Charnes. First footnote 4. Richard Levin, “The Poetics and Politics of Bardicide,” PMLA 105 (1990): 491-504. Subsequent footnotes 5. Levin, “Bashing,” 79. [A subsequent citation of the other work by this author.] 6. Levin, “Poetics,” 493. 7. Levin, “Poetics,” 499-500. |

Bibliographic entry. For second and subsequent entries by the same author(s) type three dashes (___) or three hyphens (—) instead of the name. Sort the author’s works alphabetically by title or chronologically. Whichever you choose, be consistent throughout the bibliography. (If you sort by title, disregard but don’t delete The, A, and An).

|

Levin, Richard. “Bashing the Bourgeois Subject.” Textual Practice 3:1 (Spring 1989): 76-86. ___. “The Poetics and Politics of Bardicide.” PMLA 105 (1990): 491-504. |

But do not use the dashes or hyphens for any case where the same person is cited as part of a different coauthorship. And they’re never used in combination with a spelled-out name (not ___ and William Harrison).

4. Edited work by a single author

Footnote/endnote

|

Smaller work within the volume 4. Matthew Arnold, “The Scholar-Gipsy,” in Poetry and Criticism of Matthew Arnold, ed. A. Dwight Culler (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1961), 151. A stand-alone work 5. John Milton, Paradise Lost, ed. Scott Elledge (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Smaller work within the volume Arnold, Matthew. “The Scholar-Gipsy.” In Poetry and Criticism of Matthew Arnold, ed. A. Dwight Culler, 147-153. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1961. A stand-alone work Milton, John. Paradise Lost. Edited by Scott Elledge. New York: W. W. Norton, 1975. |

5. Edited anthology

Footnote/endnote

|

5. Teresa del Valle, ed., Gendered Anthropology (London and New York: Routledge, 1993). |

Bibliographic entry

|

del Valle, Teresa, ed. Gendered Anthropology. London and New York: Routledge, 1993. |

6. A chapter or essay from an anthology

Footnote/endnote

|

6. Henrietta L. Moore, “The Differences Within and the Differences Between,” in Gendered Anthropology, ed. Teresa del Valle (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), 193-204. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Moore, Henrietta L. “The Differences Within and the Differences Between.” In Gendered Anthropology, ed. Teresa del Valle, 193-204. London and New York: Routledge, 1993. |

7. Citations of multiple works from an anthology

Treat each citation separately. Chicago style discourages cross-references.

8. An anonymous work Footnote/endnote

| 8. Job 19:23-24. The Geneva Bible: A Facsimile of the 1560 edition, introd. Lloyd E. Berry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969). |

Normally, citations from the Bible follow a particular format (book, chapter, verse, and version). The footnote here would follow that format and add publication information since a (now) non-standard historic text is being used for scholarly purposes. Bibliographic entry. Alphabetize by title, disregarding A, An, and The.

| The Geneva Bible: A Facsimile of the 1560 edition. Introduction by Lloyd E. Berry. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969. |

The Bible is not normally included in the bibliography, but in this instance the work’s status as a scholarly edition of a historical text means that a bibliographic entry is appropriate.

9. An article from an anonymous reference book Footnote/endnote

| 9. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary of English Usage. Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster, 1989, s.v. “Split Infinitive.” |

s.v. stands for the Latin sub verbo (“under the word”). Bibliographic entry. Encyclopedias and dictionaries are generally not included in the bibliography

10. An introduction, preface, or similar part of a book

Reference to a part of a book does not necessarily have to identify the part, especially if there are other citations to the text as a whole. But if citation of a specific part is indicated, here’s the format: Footnote/endnote

|

10. Paul Fussell, preface to The Great War and Modern Memory (London: Oxford University Press, 1975). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Fussell, Paul. Preface to The Great War and Modern Memory. London: Oxford University Press, 1975). |

If the part is by someone other than the author, follow this format: Footnote/endnote

|

10. W. H. Auden, introduction to The Star Thrower, by Loren Eiseley (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Auden, W. H. Introduction to The Star Thrower, by Loren Eiseley. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978. |

11. A work by two or three authors Footnote/endnote

|

11. Aaron Wildavsky and Karl Drake, “Theories of Risk Perception: Who Fears What and Why?” Daedalus 119 (1990): 41-60. 25. Lenz, Carolyn Ruth Swift, Gayle Greene, and Carol Thomas Neely, eds., The Woman’s Part: Feminist Criticism of Shakespeare (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Wildavsky, Aaron and Karl Drake. “Theories of Risk Perception: Who Fears What and Why?” Daedalus 119 (1990): 41-60. Lenz, Carolyn Ruth Swift, Gayle Greene, and Carol Thomas Neely, eds. The Woman’s Part: Feminist Criticism of Shakespeare. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980. |

12. A work by four or more authors Footnote/endnote

| 12. Randolph Quirk et al., A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language (London and New York: Longman, 1985), 217. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Quirk, Randolph, et al. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London and New York: Longman, 1985. |

13. A work by a corporate author Footnote/endnote.

Treat the organization as the author, and cite the name or a short version of it: (Modern Language Association)

|

13. National Endowment for the Arts, 1997 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts: Summary Report. Research Division Report, vol. 39 (Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 1998), 38-41. |

Bibliographic entry

|

National Endowment for the Arts. 1997 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts: Summary Report. Research Division Report, vol. 39. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts, 1998. |

14. A multivolume work—referencing the whole work Footnote/endnote

|

13. Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, 6 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948-1953). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. 6 vols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948-1953. |

15. Untitled volume in a multivolume work Footnote/endnote

|

14. Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ed. J. B. Bury (New York: Heritage, 1946), 2:923-941. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Edited by J. B. Bury. Vol. 2. New York: Heritage, 1946. |

16. Titled volume in a multivolume work

You’ve got a choice: you may give the title of the individual volume before or after the title of the multivolume work. Whichever you choose, be consistent. Footnote/endnote

|

15. Winston S. Churchill, Triumph and Tragedy, vol. 6 of The Second World War (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953), 289. or 15. Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, vol. 6, Triumph and Tragedy (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953), 289. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Churchill, Winston S. Triumph and Tragedy. Vol. 6 of The Second World War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953. or Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War. Vol. 6, Triumph and Tragedy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1953. |

17. Classics

For well-known editions of classic texts, only the name of the edition and the date of the volume are necessary (translator, place, and publisher can be left out). Footnote/endnote

| 27. Horace, Odes and Epodes, Loeb Classical Library (1978). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Horace. Odes and Epodes. Loeb Classical Library. 1978. |

For less familiar editions, full bibliographic information is given.

|

Aristotle, Politics. Translated and edited by Ernest Barker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958. |

Citation of specific passages in classic works usually is made to parts (books, sections, cantos, lines, etc.) rather than page number.

| 29. Horace, Odes, 1.3, 4.8. |

It’s common to compress this style in papers consisting mainly of classical references: 29. Horace Odes 1.3, 4.8 (additional abbreviations may also be used: see the list of standard abbreviations at the front of the Oxford Classical Dictionary). In general, division labels (book, section, canto, etc.) are not used, though abbreviations (bk., sec., etc.) may be used if deemed necessary for clarity. It may be convenient to use division names in the text: “In the sixth canto Dante meets a man transformed into a pig”).

18. Poems

Footnote/endnote. Omit page numbers when citing classic poems. Instead, cite by textual division (act, scene, canto, book, part, etc.) and line, with periods separating the numbers. However the numbers are formatted in the original, use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3). Don’t label the divisions in parentheticals or use l or ll. to denote lines, because these can be confused with numbers.

| 16. Siegfried Sassoon, “The Rear-Guard,” in The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, eds. Richard Ellman and Robert O’Clair (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973), 382, line 25. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Sassoon, Siegfried. “The Rear-Guard.” The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry. Eds. Richard Ellman and Robert O’Clair. New York: W. W. Norton, 1973. 382. |

. . . Quoting poetry Quotations of more than one line of poetry are usually set off from the text . But if you do quote more than one line in the text, indicate line breaks with a slash (or a solidus, as the Manual reminds us is the proper name) with a space on each side ( / ):

|

Gray imagines what those buried in the churchyard might have done had they lived: “Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest, / Some Cromwell, guiltless of his country’s blood.” |

Set-off quotations of poetry are often visually centered on the page (the rule of thumb is to center the longest line and work from that, but make sure to keep at least a quarter-inch left indent). Reproduce the quoted passage line for line, with the same indentation pattern and spacing between stanzas as in the original.

The best-known line of Emerson’s “Concord Hymn” comes at the end of the first stanza:

|

If you choose to begin quoting in the middle of a line of verse, convey that with extra indentation. Ellipsis follows the same format as for prose quotations, except that if you skip one or more whole lines of verse, you need to denote that with a line of em-spaced dots about the same length as the line of verse above:

Shelley builds the tension of “England in 1819” for more than a dozen lines before releasing it in the poem’s fourteenth line:

|

If a line of verse is too long to fit on a single line in your paper, you may continue the line with a further indentation of a quarter inch. Citations for set-off quotations of poetry are dropped to the first line after the quotation and, usually, centered on the rightmost letter of the longest line of verse, though they may also be flush right or indented a uniform distance from the right margin.

19. Drama

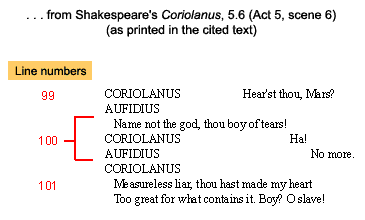

As with poetry, omit page numbers when citing classic drama. Instead, cite by textual division (act, scene, etc.) and line, with periods separating the numbers. However the numbers are formatted in the original, use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3). In parentheticals don’t label the divisions or use l or ll. to denote lines, because these can be confused with numbers (but you may use division names in the text: “Claudius dominates act 4 of the play”). Plays may be written in prose or verse. Prose presents fewer difficulties, and quotations from prose drama follow the usual Chicago conventions for prose quotations. Quoting from verse, however, is more complicated. It’s helpful to understand something about the conventions of how verse is written and printed, and how lines are counted.

Shakespeare and many other classic dramatists wrote most often in iambic pentameter, with 10-syllable lines comprising five feet of two syllables each. Such a line doesn’t necessarily end when a different character speaks. Line 5.6.100 above, for instance, consists of three utterances. Note that Line 99’s formatting indicates it’s completing a line already begun.

Although Chicago style is based on notes, the style discourages numerous footnotes or endnotes to the same works. If you have many references to a pay, for instance, put them into the text in parentheses. The following example assumes that the author and text have already been established in an initial reference.

| Aufidius taunts Coriolanus as a “boy of tears” (5.6.100). |

Bibliographic entry. There’s no need to include the original publication information for classic works unless that’s germane to your point.

|

Shakespeare, William. Coriolanus. Edited by Harry Levin. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1973. |

You may even leave such a text out of the bibliography altogether. According to the CMS (15.296), unless a particular edition is germane to your paper, plays and poems carrying standard section and line or stanza numbers may be omitted from the bibliography. In such a case, most teachers expect an initial note stating which edition(s) are being used.

. . . Quoting drama

If you are only quoting one character and a short speech, you may put the quotation within quotation marks in your text. If you’re quoting a prose passage, treat it like any prose quotation; if a verse passage, treat it like poetry:

|

Finally, Antony rises to deliver his famous funeral oration: “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; / I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. / The evil that men do lives after them; / The good is oft interrèd with their bones” (Julius Caesar 3.2.73-76). |

But as with poetry, passages of more than one line are usually set off from the text, indented as for poetry. Begin each speech with the character’s name (denoted with italics or all capitals) followed by a period and a space. Quotations of prose need no special handling; verse speeches should follow the layout of the original.

|

As with poetry generally, runover lines of dramatic verse (but not prose) should be indented an additional quarter-inch.

20. The Bible Footnote/endnote.

Cite book, chapter, and verse, and identify the version used. Abbreviate the version name in subsequent notes. The Chicago Manual of Style has a list of abbreviations for scriptural books and versions (14.34-35).

|

First note 32. Job 19.23-24. King James Version. Subsequent note 33. Job 38.36 KJV. |

If there are numerous scriptural quotations, follow the procedure noted in item 38 below for in-text parenthetical citations. The initial citation would give version information (“Quotations from the Bible are from the King James Version”); subsequent references would be placed in the text: (Job 38.36). Bibliographic entry. The Bible is not normally included in the bibliography.

21. Letter in a published collection Footnote/endnote

| 19. Niccolò Machiavelli to Francesco Vettori, 10 December 1513, Machiavelli: The Chief Works and Others, trans. and ed. Allan Gilbert (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1965), 2:927-931. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Machiavelli, Niccolò. Letter to Francesco Vettori, 10 December 1513. In Machiavelli: The Chief Works and Others, translated and edited by Allan Gilbert, 2:927-931. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1965. |

22. Public documents

There are many kinds of public documents. Here we present guidance with the most common types, focusing on American public documents. In some cases I have chosen one of several acceptable formats (there is a good deal of leeway in CMS treatment of citations of public documents). See the Manual for fuller treatment. Information supplied in a reference What information you must supply and how you order it may vary. A full reference would include these elements, though not necessarily in this order:

- Governmental territorial division (country, state, etc.) issuing the document.

- Legislative body, executive department, court or other top-level author.

- Subsidiary offices or departments.

- Title of the document or collection.

- Individual author (editor, compiler) if given.

- Identification number or other reference referring to the specific document.

- Publisher, if different from the issuing body.

- Date.

- Page or textual division, if relevant.

Not all references will have all this information. For economy, some categories may be omitted if obvious from context or deemed unnecessary. References to Senate documents, for instance, often eliminate mention of the Congress. As always, whatever decisions are made about format, consistency should be maintained throughout a work’s notes and bibliography. Publication information Most U.S. government publications are printed by the Government Printing Office (Washington, D.C.). Publication information for government documents may format this printing information in a variety of ways (for instance by abbreviating to GPO or leaving off the city). The Chicago Manual recommends that a work’s references and bibliography choose one format and use it consistently, regardless of how the publication information is formatted in the source. Consistency matters more than the particular format. WriteMyEssay.nyc recommends this version: Washington, D.C.: GPO, 2000 The Internet Most U.S. government public documents are now accessible online via the Government Printing Office’s website (http://www.access.gpo.gov/). Since references are meant to help readers locate texts, WriteMyEssay.nyc recommends including link information to public documents accessible through the official GPO website (not private third-party sites). Such link information is likely to become a standard part of references to public documents. For general help with Internet citations, consult the guidelines below.

23. The United States Constitution

Cite by article or amendment, section, and clause (as needed). Abbreviations and Arabic numerals are customary. Footnote/endnote

| 23. U.S. Constitution, preamble. 24. U.S. Constitution, art.1, sec. 8. 25. U.S. Constitution, amend. 14, sec. 1 |

Note: this is the general format for citing the Constitution. Citations in predominantly legal works follow different guidelines: 23. US Const, Amend XIV, § 1. See the Chicago Manual (15.312) for more details, or consult a guide like the University of Chicago Manual of Legal Citation. Page numbers or bibliographic information for printed texts of the Constitution are not given. Bibliographic entry. The Constitution is not listed in the bibliography.

24. Congressional documents

Documents include the Congressional Record; committee reports, hearings, and prints; bills and statues; and other documents. Publication information (city, publisher) is not necessary. Many documents issue from Congressional committees. Use the full committee name even when a sub-committee is identified as the document author. For other congressional documents, include the number and session of Congress, the house (S. stands for Senate, H. and H.R. for House of Representatives), and the type and number of the publication. Types of congressional publications include public laws (P.L. 106-11), bills (S 87, H.R. 213), resolutions (S. Res. 14, H. Res. 29), reports (S. Rept. 106-109, H. Rept. 103), and documents (S. Doc. 144, H. Doc. 282). Congressional Record Since 1873 the Congressional Record (often abbreviated as Cong. Rec. in notes) has served as a daily record of congressional activities and debates. Cite the permanent bound version when possible, and identify daily or biweekly editions (which are likely to have different pagination) when citing them. If, as will usually be the case, the body of your paper identifies the speaker and the subject of a speech recorded in the Congressional Record, the note and reference may take this form: Footnote/endnote. You may include a year, year and date, or skip this information altogether, as the volume and page will locate the source.

| 24. Cong. Rec., 106th Cong., 2nd sess. 2000, 146, no. 111:H7826-H7827. |

Bibliographic entry

| Congressional Record . 106th Cong., 2d sess., 2000. Vol. 146, no. 111. |

If speaker or subject are not clear from your use of the material, include this information in the note and reference: Footnote/endnote. The date may be included.

| 24. Representative David Bonior of Michigan speaking on the floor of the House on the Chinese government’s jailing of 81-year-old Catholic bishop Zeng Jingmu, 106th Cong., 2d sess., Cong. Rec. (19 Sept. 2000), 146, no. 111:H7826-H7827. |

Bibliographic entry

| U.S. House. Representative David Bonior of Michigan speaking on the Chinese government’s jailing of 81-year-old Catholic bishop Zeng Jingmu. 106th Cong., 2d sess. Congressional Record (19 Sept. 2000). Vol. 146, no. 111. |

Reports and documents Reports and documents of the Senate and the House are numbered and bound in the serial set. The abbreviations Rept. (Report), Doc. (Document), S. (Senate) and H. (House of Representatives) are used. Footnote/endnote. The specific page reference is included if appropriate.

| 29. House Committee on the Judiciary, Internet Nondiscrimination Act of 2000: Report together with Minority Views (to accompany H.R. 3709), 106th Cong., 2d sess., 2000, H. Rept.106-609, 23-24. |

Bibliographic entry

| U.S. House. Committee on the Judiciary. Internet Nondiscrimination Act of 2000: Report together with Minority Views (to accompany H.R. 3709). 106th Cong., 2d sess., 2000. H. Rept.106-609. |

Hearings Footnote/endnote. The specific page reference is included if appropriate.

| 32. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, United Nations Peacekeeping Missions and Their Proliferation: Hearing before the Subcommittee on International Operations of the Committee on Foreign Relations, 106 Cong., 2nd sess., 2000, 137-142. |

Bibliographic entry

| U.S. Senate. Committee on Foreign Relations. United Nations Peacekeeping Missions and Their Proliferation: Hearing before the Subcommittee on International Operations of the Committee on Foreign Relations. 106 Cong., 2nd sess., 2000. |

Committee prints Footnote/endnote. Include page reference if appropriate.

| 33. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Country Reports on Economic Policy and Trade Practices, report submitted to the Committee on Foreign Relations, Committee on Finance of the U.S. Senate and the Committee on International Relations, Committee on Ways and Means of the U.S. House of Representatives by the Department of State in accordance with section 2202 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, 106th Cong., 2d sess., 2000, Committee Print 45, 117-118. |

Bibliographic entry

| U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Country Reports on Economic Policy and Trade Practices, report submitted to the Committee on Foreign Relations, Committee on Finance of the U.S. Senate and the Committee on International Relations, Committee on Ways and Means of the U.S. House of Representatives by the Department of State in accordance with section 2202 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. 106th Cong., 2d sess., 2000. Committee Print 45. |

Bills (and resolutions) Congressional bills are proposed laws. Bills and resolutions are cited in notes but not usually not included in the bibliography. Initially, bills are published as pamphlets. Footnote/endnote

| 47. House, Internet Access Charge Prohibition Act of 2000, 106th Cong., 2d sess., H.R. 1291. |

Or, if the title of the bill appears in the text, it may be left out of the note:

| 47. H.R. 1291, 106th Cong., 2d sess. |

Bibliographic entry As noted, bills and resolutions are not usually included in the bibliography. If you do list one, the bibliographic entry should include the title:

| U.S. House. Internet Access Charge Prohibition Act of 2000. 106th Cong., 2d sess., H.R. 1291. |

25. Statutes or laws

Statutes are published in several different sources, and the particular source must be specified. Statutes may be included in the bibliography, but they are often cited only in notes. Be consistent. Public laws Statutes are first published separately, being referred to as slip laws or public laws. Footnote/endnote. Include page reference(s) if appropriate.

| 35. Border Smog Reduction Act of 1998, Public Law 286, 105th Cong., 1st sess., (27 October 1998), 3. |

Bibliographic entry

| Border Smog Reduction Act of 1998. Public Law 286. 105th Cong., 1st sess., 27 October 1998. |

Statutes at Large After individual publication, laws are collected in bound volumes entitled United States Statutes at Large. Footnote/endnote. Include specific page reference(s) if appropriate.

| 48. Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, U.S. Statutes at Large 102 (1989): 4194, 4227. |

Bibliographic entry

| Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. U.S. Statutes at Large 102 (1989): 4181-4545. |

U.S. Code Eventually laws are incorporated into the United States Code. Footnote/endnote. Include particular section reference(s) if appropriate.

| 57. Lobbying Disclosure Act, U.S. Code, vol. 2, sec. 1602. |

Bibliographic entry

| Lobbying Disclosure Act. U.S. Code. Vol. 2, secs. 1601-1612. |

26. Presidential documents

These include executive orders, addresses, and public papers, and other documents. These are published in The Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents the Federal Register, which is also available in microfiche (and, WriteMyEssay.nyc adds, online), and in the Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. Footnote/endnote

| 26. William J. Clinton, “Letter to Congressional Leaders on Permanent Normal Trade Relations Status With China,” Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents 36, no. 4 (31 January 2000), 133-179. 27.William J. Clinton, “Memorandum on Electronic Commerce,” Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1998), pp. 2100-2102. |

Bibliographic entry

| Clinton, William J. “Letter to Congressional Leaders on Permanent Normal Trade Relations Status With China.” Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents 36, no. 4 (31 January 2000), 133-179. _____. “Memorandum on Electronic Commerce.” Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1998 |

27. Executive department, administrative agency, and government commission documents

Discretion is allowed in how to refer to an issuing body. Census Bureau publications, for instance, need not list the Department of Commerce as a parent organization. In general, familiar agencies or bureaus may be cited as the issuing body; citations of less-familiar ones should include the parent department. Sub-units within agencies often issue documents, and these should be listed in top-down order. Footnote/endnote

| 28. U.S. National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare, Building a Better Medicare for Today and Tomorrow (Washington: GPO, 1999), 117-122. 27. U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Division of Voluntary Programs, OSHA Handbook for Small Businesses, rev. ed. (Washington, D.C.: Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 1990), 23. |

Bibliographic entry

| U.S. National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare. Building a Better Medicare for Today and Tomorrow. Washington: GPO, 1999. U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Division of Voluntary Programs. OSHA Handbook for Small Businesses, rev. ed. Washington, D.C.: Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 1990. |

28. Federal and state court decisions

Court decisions are usually not included in the bibliography. Supreme Court Supreme Court decisions are published officially in the United States Supreme Court Reports (abbreviated U.S.). They are also published in the Supreme Court Reporter (Sup. Ct.). Citations should preferably be to U.S., though Sup. Ct. may be used if necessary, or both sources may be cited. Footnote/endnote. Include page reference if pertinent.

| Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200, 115 S.Ct. 2097 (1995). |

Federal Court Lower federal court decisions are published officially in the Federal Reporter (abbreviated F.). If the decision is in a supplement (Supp.) or a series (2d, 3rd, etc.) other than the first, this should be noted. The court and date are identified at the end of the citation. Footnote/endnote

| Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. United States Army Corps of Engineers, 109 F. Supp. 2d 30 ( D.C. Cir. 2000). |

State Court Similar format: the case name, reporter reference, state, and year. Footnote/endnote

| Foley v. Honeywell, 488 N.W.2d 268 (Minn. 1992). |

In general, subsequent citations of court decisions may be shortened to case titles: Adarand Constructor, Inc. v. Pena, 47.

29. A magazine article

Some periodicals may use different titles for articles on the contents page and at the beginning of the article itself. In such cases, use the title from the contents page. Footnote/endnote

|

21. Evan Thomas and Bill Turque, “Gore: The Precarious Prince,” Newsweek, 21 August 2000, 38-41. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Thomas, Evan and Bill Turque. “Gore: The Precarious Prince.” Newsweek, 21 August 2000, 38-41. |

30. An anonymous magazine article Footnote/endnote

|

22. “Preserving Life on Other Planets,” The Economist, 29 July 2000, 79. |

Bibliographic entry

|

“Preserving Life on Other Planets.” The Economist, 29 July 2000, 79. |

31. A newspaper article Footnote/endnote

|

23. Jim Hoagland, “The Concord and the Kursk,” Washington Post, 20 August 2000, B7. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Hoagland, Jim. “The Concord and the Kursk.” Washington Post, 20 August 2000, B7. |

32. An unsigned article or editorial Footnote/endnote

|

24. “A Right to Discriminate?” Washington Post, 20 August 2000, B6. |

Bibliographic entry

|

“A Right to Discriminate?” Washington Post 20 August 2000, B6. |

33. A pamphlet Treat a pamphlet like a book.

34. Multiple citations in one note

The Chicago Manual of Style recommends avoiding excessive notes when possible. If a sentence has several cited texts, it is generally wise to gather the citations in one note at the end of the sentence. Footnote/endnote

|

This belief, that modern capitalism rewards firms that develop humanistic structures and cultures, has become the conventional wisdom of management studies, expressed in best-selling works over the past twenty years by scholars like Tom Peters, Robert Waterman, William Ouchi, W. Edwards Deming, Peter Senge, and many others. 35. See for instance Thomas J. Peters and Robert H. Waterman, Jr., In Search of Excellence (New York: Harper & Row, 1982); William G. Ouchi, Theory Z (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1981); W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study, 1986); and Peter Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (New York: Doubleday, 1990). |

Likewise, a paragraph containing several short quotations need not give a citation for each of them, especially if they are from the same text. Avoid confusion by matching the number and order of citations to the number and order of quoted passages. Bibliographic entry. Each work, of course, is entered in the bibliography separately.

35. A translation Footnote/endnote

|

Galileo Galilei, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems—Ptolemaic and Copernican, trans. Stillman Drake (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1953), 147-161. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Galilei, Galileo. Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems—Ptolemaic and Copernican. Translated by Stillman Drake. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1953. |

36. A second or subsequent edition Footnote/endnote

As usual.

|

29. Glynne Wickham, The Medieval Theatre, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 222. |

Bibliographic entry

|

Wickham, Glynne. The Medieval Theatre. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987. |

The name of an editor, translator, or compiler (if any) is placed before the edition.

37. Indirect source Footnote/endnote.

Include as much information as you can about the original source.

| 30. Jakob Burckhardt, quoted in Hanna Fenichel Pitkin, Fortune Is a Woman: Gender and Politics in the Thought of Niccol� Machiavelli (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 25. 31. Alistair Horne, To Lose a Battle (Boston: Little, Brown, 1969), 56-57. Quoted in William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, vol. 2, Alone: 1932-1940 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1988), 55. |

Bibliographic entry. If you use a text only indirectly, don’t include it in the bibliography.

38. Abbreviations for frequently cited works

The Chicago Manual of Style allows in-text parenthetical citations of frequently cited works. This is common, for instance, in extended studies of an author. A note attached to the first citation from the author explains the abbreviations used.

|

The citation in the body of the essay Necessity rather than ethics drives political action, Machiavelli says: “It is necessary for a prince to know well how to use the beast and the man” (P 69). The note 1. Quotations from Machiavelli are cited in the text with the abbreviations listed below, noting text and page reference.

|

If ten or more abbreviations are used, these should be gathered together in a list and placed nears the endnotes (or bibliography). If the list is brief (a half-page or less), it is placed after the heading “Notes” and before the notes themselves.. If the list is long, it is placed on a page or pages preceding the notes or bibliography, with the heading “Abbreviations” in the same style as the Notes. The list is prefaced with a brief explanation, and arranged in two columns: abbreviations on the left, and full bibliographic references on the right. You may use whatever abbreviations are convenient (usually acronyms or the first letter of a text).

39. Missing bibliographic information

Use the following abbreviations for information you can’t supply.

| n.p. n.p. n.d. | No place of publication given No publisher given No date of publication given |

If both place and publisher information is lacking, use just one n.p. Put the abbreviation where the information would customarily go.

|

Kiefer, Frederick. Fortune and Elizabethan Tragedy. N.p.: Huntington Library, 1983. |

If the missing information is known but not given, it may be included in brackets.

|

Carter, Thomas. Shakespeare and Holy Scripture. New York: AMS Press, [1970]. |

If you’re uncertain about the accuracy of the information, use a question mark. If a date is approximate, precede it with c. for circa (“about”).

|

[Norton, Thomas?]. A Declaration of Favourable Dealing by Her Majesty’s Commissioners for the Examination of Certain Traitors. London, c. 1583. |

Especially for old works (pre-1900), missing publication information may simply be omitted.

Chicago Internet notes and references

The most recent edition of the Chicago Manual of Style, published in 1993, predates the widespread use of the Internet and gives little guidance on Internet citations. The examples here apply Chicago style to online sources, adding additional date information in recognition of the dynamic nature of online texts. Many citations of online sources in college papers are inadequate. Here’s an all-too-common example: www.hoovers.com. What’s missing? Lots—information about the type of online resource, a specific URL to a particular document, and data on author, title, when online material was posted, and when you retrieved it (that means when you downloaded or printed the information, not when you wrote it into your paper). It’s important to provide dates because the web is a dynamic medium, with content and web sites constantly changing. References to online documents follow the same basic Chicago format: alphabetization by author, a title, and publication information. One difference: references to online documents typically have two dates, the date the material was published or updated, and the date it was retrieved. Since the web is a dynamic medium with content and web sites constantly changing, it’s helpful to your reader to note posting and retrieval dates.

The page problem One complication of online documents is that they usually lack page numbers, so it’s not easy to point readers to particular passages. In order to direct readers as closely as possible to the right source passage, use whatever divisions the work is formatted in. Look for division numbers, section titles or for words like Introduction and Conclusion. In a pinch count paragraphs: “para. 7.”

What’s your source? Another source of confusion with online documents is the profusion of copies of texts. With the way the Internet works, anyone can post any document, accurate or not, for public access. In general, make sure that if you’re quoting from a text you try to track down the copyright holder or other responsible organization, rather than taking the text and URL from a personal page or other idiosyncratic source. For instance, cite government documents from the Government Printing Office’s website (http://www.access.gpo.gov/) or similar source. Doing so increases the chances you’ll get an accurate copy, and it reassures readers about your scholarly care. For more on online research, see the WriteMyEssay.nyc section on Research and the Internet.

Here are the types of electronic sources detailed below:

E1. Private or personal web site Footnote/endnote

| 11. Leah Cunningham, “My Mahir Shrine!!” N.d., <http://www.geocities.com/Hollywood/Film/9787/> (17 July 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Cunningham, Leah. “My Mahir Shrine!!” N.d. <http://www.geocities.com/Hollywood/Film/9787/> (17 July 2000). |

Personal web sites are often not listed in the bibliography.

E2. Organizational or corporate web site Footnote/endnote

|

7. American Political Science Association, APSANET: The American Political Science Association Online, 1 July 2000, <http://apsanet.org/> (23 August 2000). 8. Ford Motor Company, home page, 29 September 2000, <http://www.ford.com/> (29 September 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

|

American Political Science Association. APSANET: The American Political Science Association Online. 1 July 2000. <http://apsanet.org/> (23 August 2000). Ford Motor Company. Home page. 29 September 2000. <http://www.ford.com/> (29 September 2000). |

E3. Online book Footnote/endnote

| Previously published book 3. Sarah Orne Jewett, The Country of the Pointed Firs (1910; online edition, Bartleby.com, 1999), <http://www.bartleby.com/125/> (15 August 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Jewett, Sarah Orne. The Country of the Pointed Firs. 1910. Online edition, Bartleby.com, 1999. <http://www.bartleby.com/125/> (15 August 2000). |

E4. Article in an online journal or magazine Footnote/endnote

|

4. David Edelstein, “Pols on Film,” Slate Magazine (18 August 2000), <http://slate.msn.com/MovieReview/00-08-18/MovieReview.asp> (20 August 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Edelstein, David. “Pols on Film.” Slate Magazine, 18 August 2000. <http://slate.msn.com/MovieReview/00-08-18/MovieReview.asp> (20 August 2000). |

E5. Newspaper article Footnote/endnote

|

5. Maureen Dowd, “Stop That Canoodling!” New York Times on the Web, 20 August 2000, <http://www.nytimes.com/library/opinion/dowd/082000dowd.html> (20 August 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

|

Dowd, Maureen. “Stop That Canoodling!” New York Times on the Web, 20 Aug. 2000. <http://www.nytimes.com/library/opinion/dowd/082000dowd.html> (20 Aug. 2000). |

E6. Government publication Footnote/endnote

|

6. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “Commission Staff Issues Accounting Bulletin on Revenue Recognition,” press release, 3 December 1999, <http://www.sec.gov/news/press/99-162.txt> (17 July 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

|

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “Commission Staff Issues Accounting Bulletin on Revenue Recognition.” Press Release. 3 Dec. 1999. <http://www.sec.gov/news/press/99-162.txt> (17 July 2000). |

For other kinds of public documents, apply these Internet elements—the URL and retrieval date—to the formats for public documents above.

E7. Short work in larger work or database Footnote/endnote

|

7. “Cuckoo Song,” in The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250�1900, ed. Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch (1919; online edition, Bartleby.com, 1999), <http://.www.bartleby.com/101/1.html> (16 August 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

|

“Cuckoo Song.” The Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250�1900. Ed. Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch. Oxford: Clarendon, 1919. Online edition, Bartleby.com, 1999. <http://.www.bartleby.com/101/1.html> (16 August 2000). |

If the title of the short work is noted in the body of the paper, the note and bibliographic reference could refer simply to the larger book.

E8. Other web materials Footnote/endnote

|

8. “Microstrategy, Inc.,” chart, Washington Post, 20 August 2000, <http://financial.washingtonpost.com/graph.asp?ticker=MSTR> (20 August 2000). |

Bibliographic entry

| “Microstrategy, Inc.” Chart. Washington Post, 20 August 2000. <http://financial.washingtonpost.com/graph.asp?ticker=MSTR> (20 August 2000). |

E9. Forum or conference posting Footnote/endnote

|

9. William Jensen, “Re: Question About Grading Essays,” 17 April 2000, <http://tychousa.umuc.edu/BMGT110/5218/class.nsf/conference/value.htm> (18 July 2000). |

Use of the source material in the body of the essay should clarify the nature of the source. Bibliographic entry. Postings not accessible to the public are generally not included in the bibliography. Public postings may be included.

E10. Email Footnote/endnote

|

9. Peter Johnson, email to author, 3 October 2000. |

Bibliographic entry. Following CMS style for personal communications, email is generally not listed in the bibliography (CMS 15.269).

Substantive notes

Sometimes a writer wants to discuss a topic or mention something that doesn’t really fit in the body of the paper: a discussion of sources, for instance, that seems too narrow to fit in the body. For such instances one may use substantive, or discursive, notes. These generally follow the same format and share the numbering of other endnotes or footnotes in the paper, though lengthy works with very extensive documentation (unlikely for undergraduate writing) may put bibliographic in endnotes and substantive notes in footnotes. Here are some typical kinds of comments that might go in notes.

An acknowledgment or thanks, numbered “1” and attached to the title or first sentence of the essay.

|

1. Thanks to the Society of Junior Fellows for generous research support. |

A note on method, attached to the first use of pertinent material.

|

8. Pseudonyms have been used to preserve the confidentiality of interviewees. 2. In 1998 Allient Computing changed its accounting procedures, making comparison with previous years impractical. |

A note that mentions or evaluates sources.

|

1. On this difficult subject see Otto Demus, Byzantine Art and the West (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1970). The Larousse Encyclopaedia of Byzantine and Medieval Art, ed. Ren Huyghe (Paris, 1958), supplies useful documentation on other influences from the Near and Far East including Persian, Egyptian, Indian and Chinese Art of earlier periods. |

|

Glynne Wickham, The Medieval Theatre, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987, 224. |

This kind of substantive note requires special handling. If a text mentioned here has already been cited in full earlier in the work, it may receive a short reference here:

|

27. As an example of this movement, the interpretive gulf between Tillyard and Greenblatt, “Circulation,” shows how radically scholarly fashion can change from one generation to the next. |

If a work is being cited for the first time in a substantive note, the bibliographic reference is supplied in the note. It may be given in parentheses, worked into the text, or supplied at the end of the note. If it is given in parentheses, then brackets [] are used to enclose the publication facts (city, publisher, year).