How to Avoid Problems with Using Source Material

Table of Contents

College essays stand or fall based largely on their use of evidence. In this section we’ll consider how to do research, how to avoid common problems with using source material, and how to follow major citation styles for the humanities, the social sciences, and the natural sciences.

We begin where most college students now begin the task of doing research: with the Internet.

Surfing the Internet

The Internet—that intoxicating, globe-girdling kaleidoscope of thousands of linked networks, millions of users, billions of pages, and no one in charge—is a modern-day sorcerer’s apprentice. With just a few keystrokes and mouseclicks, anyone anywhere anytime can summon up kajillions of documents on any topic—electronic versions of original texts, online journals, published and unpublished articles, cutting-edge research, crazy diatribes, high-school essays, newsgroup posting, commercial sites, crackpot pseudo-research—plus of course a million tangents just one click away. The Internet is an unending riot of fact, fiction, and noise on any topic you can dream of.

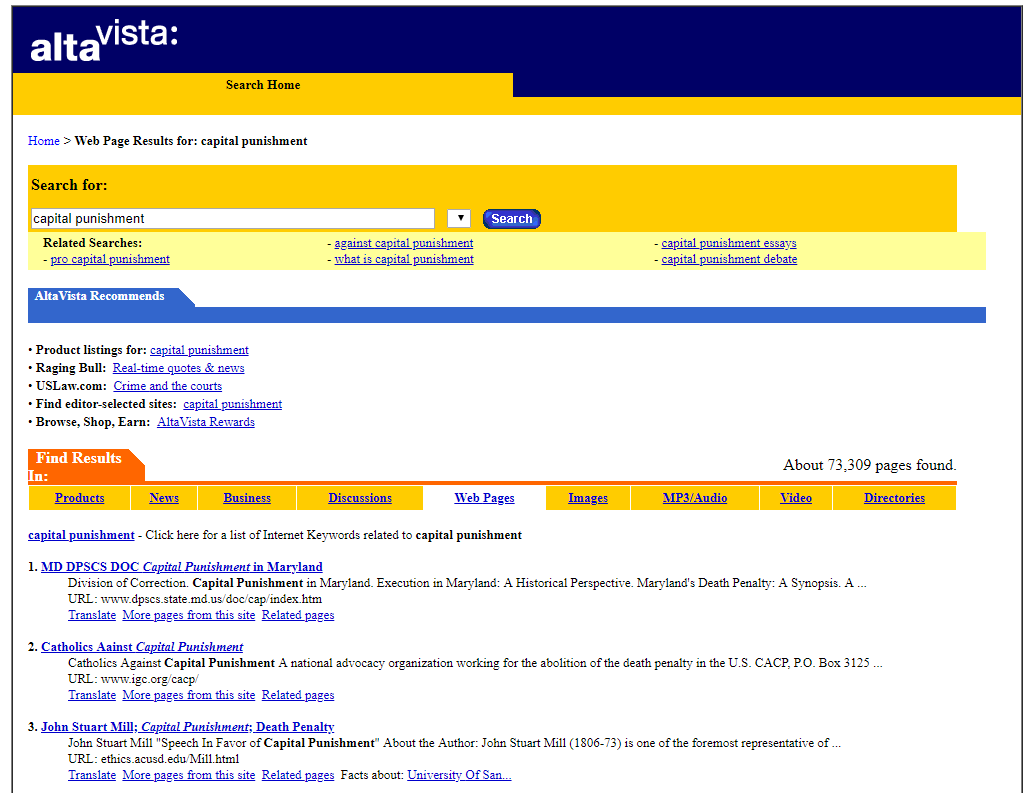

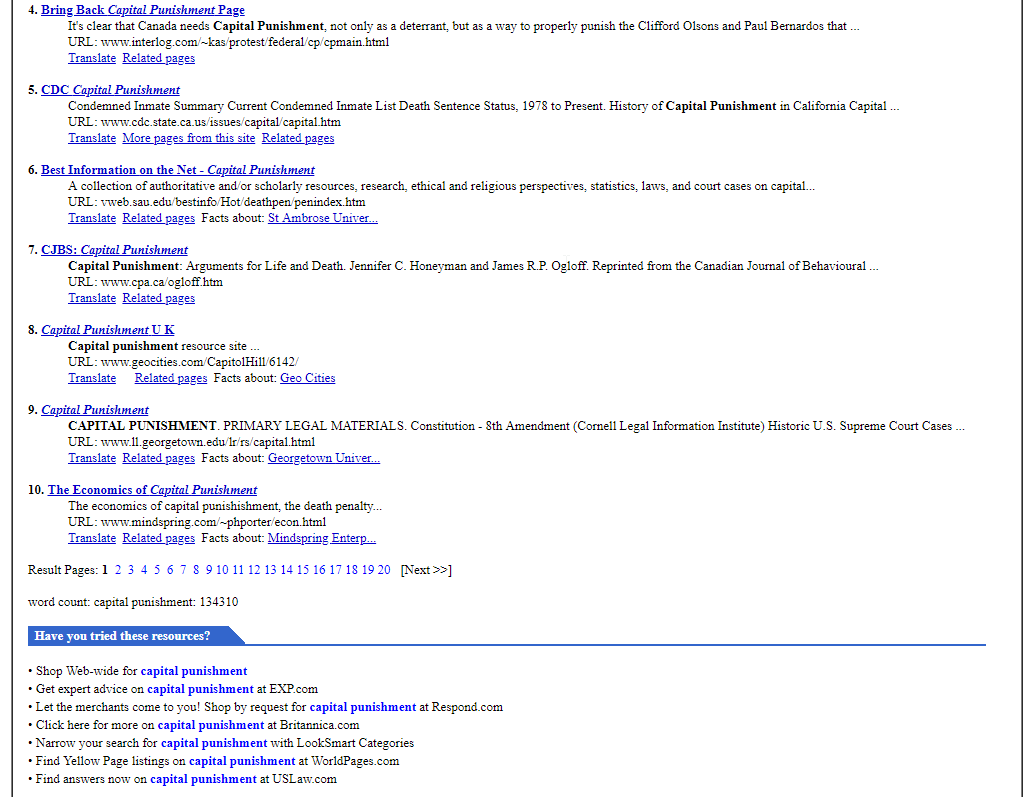

For instance, suppose you’re writing a research paper on capital punishment. You might run the term through a popular search engine like Alta Vista, with results something like this:

So what now? Which of the “about 73,309 pages found” should you start looking at? Should you check out “Product listings for: capital punishment“? (What’ve they got—good deals on electric chairs?) What about the related searches (pro capital punishment, against capital punishment, etc)? They all sound potentially interesting. The “Alta Vista recommends” section also has some interesting links—editor-selected sites, news, the USLaw.com site, “Crime and the Courts” (hmm, what’s USLaw.com?). What about that stuff at the bottom? Expert advice, Britannica, narrow the search, yellow page listings (??), there’s USLaw.com again. . . .

And we haven’t even gotten to the search results yet. Check out the first 10—hmm, tons of stuff on capital punishment in Maryland . . . Catholics, John Stuart Mill, Canada, California, “Best Information on the Net,” an article from a journal, court cases, economics. . . .

Holy schlamoley. What now?

Searching the Internet by just jumping in—without a plan, without experience, without expert help—is a crap shoot. But it happens all the time. Students enter terms in their favorite search engine, get back a mountain of results, randomly follow a few leads, and all too often end up with a handful of documents or sites that just happened to be among the first 20 or so listed in the search results. These items often get woven into a paper regardless of their quality, credibility, scholarly status, relevance, or coherence.

The result is that too much student research on the Internet resembles the proverbial monkey pounding away at the keyboard. Give the monkey enough time and he’ll crank out Hamlet; give a student Internet access for 15 minutes and she’ll crank out the raw material for a paper on capital punishment, with references to John Stuart Mill, Canada, the history of capital punishment in Maryland, and a list of current death row inmates in California.

That might look like research, but it’s not.

One way of making sense of the Internet for college research is to distinguish two kinds of online searches: open searches and closed searches. Open searches look through the vast amounts of publicly-accessible material on the web, using free search engines and subject directories. They are primarily useful for informal and introductory research, for brainstorming, and for filling in missing details (when you want to know the population of Brazil, or the speed of light in water, or the year John Donne wrote “The Flea”).

Closed searches, by contrast, look not through the whole web but through limited, edited collections. Typically one pays for a closed search, though since licenses and fees have often been arranged by one’s organization (a college library or corporation, for instance), a closed search can feel free to an individual user. Closed searches are primarily useful for formal research, for instance when you need to search for recent publications in an academic field.

Both open and closed searches are useful for anyone engaged in research, but they achieve different things and require different search strategies. Closed searches won’t tap into the richness of the web, and open searches won’t reliably produce scholarly material on academic topics. Many undergraduates, however, blur the two kinds of searches together, with the predictable result of bizarre tangents, a mishmash of references, and a lack of scholarly gravitas.

Open searches

The Internet is a superb brainstorming tool. Say, to continue our example, that you think you might want to write about capital punishment for a course in American politics or philosophy or criminal justice. But at the moment, that’s all you know—you’re no expert on the topic, you’re not sure about the status of the law in the U.S. (is capital punishment a federal issue? A state issue? Both?) or what other countries do. You don’t know much, if anything, about the history of capital punishment; nor are you up on recent controversies—though you do recall hearing something about recent brouhahas in Illinois and Texas, you think.

The Internet can take your vague interest in a topic and, after a couple of hours of searching and reading, give you a thorough grounding and a dozen avenues for further exploration. That’s one of the most amazing things about it—it offers instant crash courses in anything you want to learn about, from t = 0 to right this instant.

There’s no single “best” search tool. First of all, none of them covers the whole web or anything close to it. The web is constantly changing, and web pages come and go faster than the speediest search engine can track the changes (resulting in the beloved 404 error when a search engine tries to direct you to a page that’s disappeared). No search engine, even the biggies like Alta Vista and Google, manage to track more than maybe a tenth or so of the ever-growing number of web pages in existence. Still, 10% of one billion or so web pages will produce a lot of hits.

Second, before launching into a brainstorming search, you should know something about how different kinds of search tools work. There are two main kinds: search engines and subject directories. Search engines, like the term implies, are mindless robots that crawl endlessly through the Internet, filing away information about every page they come across, including the page’s full text. But search engines aren’t really meant to organize the data for you. You’d like some information on capital punishment? A search engine will give you a truckload. You’re looking for the complete text of Furman v. Georgia, the 1972 Supreme Court decision that declared the death penalty unconstitutional? A search engine will give it to you fast. But if you’re not sure exactly what you’re looking for—say you just want to find a high-quality site from a reputable source as a gateway to learning about the topic—well, good luck sorting through all 73,309 pages.

By contrast, subject directories like Yahoo! and the Open Directory Project (which search engines like Alta Vista and AOLsearch partner with) are like vast libraries that have been organized just for you. They compile information into categories—not automatically by robots, but thanks to the labors of armies of unsung and underpaid (or unpaid) editors. Yahoo!, for instance, organizes its contents into fourteen main categories (Arts & Humanities, Business & Economy, Computers & Internet, Education, etc.), and then breaks these down further. Things get listed wherever Yahoo!’s subject editors feel they fit. Subject directories don’t try to present exhaustive guides to the Internet—just to the best sites for each category. Nor do subject directories index complete sites. Thus a subject directory is not a good choice if you want to find sites that include particular text, like a particular court case or a name or a date. But subject directories offer something very useful for scholarly research: summaries and annotations that make it easier to decide whether a particular site is worth a visit. A subject directory like Yahoo! is the best quick way to find high-quality sites on a given topic (for instance, try searching Yahoo! for “essay writing help”).

If search engines are the Internet’s muscle cars, bristling with raw speed, subject directories are its minivans—not as much horsepower but better for running many research errands. The best search strategy is to be familiar with both kinds of search tools and use them in tandem.

| Recommended search engines and subject directories

Search engines (best for exhaustive searching for particular data like names, terms, and text)

|

|

Subject directories (best for exploring particular subjects in depth and finding high-quality sites)

|

(This list is from the UC Berkeley Teaching Library Internet Tutorial. The latest version, plus links to the rest of the tutorial, can be found at http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/TeachingLib/Guides/Internet/ToolsTables.html. The Berkeley guide provides a great deal of additional information on each of the sites listed above, including combining searches, advanced search strategies, and using meta-search engines.)

Choosing a search engine or subject directory is just the first step in conducting an open search. Learning how to use these tools is even more important. For instance most basic search engines like Alta Vista and Google recognize such symbols as +, –, and quotation marks (which denote phrases) to help make searches more precise: If you want to search, for instance, for the phrases “Supreme Court” and “capital punishment” you’d enter this: +”Supreme Court” +”capital punishment.”

But I recommend moving a step further, to learning how to conduct boolean searches. A boolean search, in which you can use logical connectors to craft complex search statements, allows you to conduct finely tuned searches that eliminate a lot of noise. It’s not particularly difficult after a few minutes of study. Here are some quick tips for Alta Vista Advanced Search (http://www.altavista.com/cgi-bin/query?pg=aq&stype;=stext). Besides boolean searching, Advanced Search lets you decide what sorting criteria results are returned for you. This is a very powerful feature; it’s another way to increase the chances that you’ll find what you’re looking for.

Quick tips for Alta Vista Advanced Search and other boolean searches

|

All this can help you narrow down searches. But there comes a time in all serious scholarly research when you need to move from public databases to professionally maintained collections. That’s the time for closed searches.

Closed searches

The point of closed searches is to enable serious and credible scholarly research. If you’re investigating representations of gender in Elizabethan drama, or recent advances in gene sequencing, or theories of computation, you’re not going to find a lot of useful information with a search engine like Google or a subject directory like Yahoo! (though admittedly, as noted, good subject directories make excellent starting points for exploring a particular topic). To come back one more time to our earlier example of a research paper on capital punishment, once you’ve zeroed in on a particular topic, you’ll want to turn to a closed search. Let’s suppose you’ve decided to focus on one aspect of the debate over capital punishment—why the Supreme Court ruled the death penalty unconstitutional in 1972 and then in effect changed its mind four years later. Well, you need to find out what other scholars have said about this. What other literature is already out there on your topic? What are the major perspectives and controversies among scholars? Are there primary materials in archives that should be consulted? All of these questions are best explored by searching law reviews, academic journals, and other scholarly repositories of information.

The first piece of advice for students trying to conduct effective closed searches is simple: use your library’s home page as your main research portal. Libraries have learned how to integrate the Internet into their holdings, and the college library now serves as a crucial research gateway to many databases. My school, for instance, offers access to a dozen different periodical indexes (not to mention a myriad of other research tools like online dictionaries, encyclopedias, reference books, links to online newspapers and magazines, and much more). Some of these periodical indexes list only citations (Medline, ERIC, MLA Bibliography, among others) and some are full-text like IDEAL and JSTOR. One of my favorites is Lexis-Nexis. It provides a massive amount of political, legal, and business information, full-text search and retrieval of major newspapers and magazines from around the world, and lots more.

The only hard part in all this is learning how to use the search tools. Most libraries provide online tutorials and FAQs which you can find from the library’s home page, and of course asking a real live reference librarian always works well. One tip: most college libraries can be accessed remotely by authorized users (i.e., you the student). Directions are usually available at the library’s home page or from a librarian. The advantage of remote access is that you can tap into all the library’s licensed databases from wherever you happen to be, on campus, off campus, or across the country.

A final word on open and closed searches: it’s useful to think of research as a process of spiraling in towards a narrow, precise target. Early on, use open searches to learn about a subject. Search engines will give a sense of how the subject plays in the popular mind. Subject directories will point the way to good scholarly sites that could serve as gateways for further research. Once you’re ready to start thinking about specific topics and arguments, it’s time to move most of your efforts to closed searches, and for that you’ll want to become familiar with your library’s online search tools. But as you get better and better at diving into the vasty depths of the Internet, don’t forget the invaluable help real people with expertise can provide. Ask librarians, grad students, and professors to help get you pointed in the right direction.

Citing web sites

Most students’ citations from the web are inadequate. Here’s the kind of citation one sees all too often: www.hoovers.com. But if you follow this link, you’ll find it simply gets you to the home page of a big business database, full of detailed information on hundreds of industries and thousands of companies, and with links to tens of thousands of articles. Knowing the home page doesn’t help you track down a statistic you want to double-check (which, remember, is the point of scholarly citation—to allow others to reproduce and check your work).

So what is missing from such a citation? Lots of important stuff: information about the type of online resource, a specific URL, data on author, the title of the document and a description, a publication or posting date, and a retrieval date, to name the key elements. Without this data the reference is useless in an academic sense.

Citation information doesn’t automatically come with a downloaded web page, or with a passage copied from a page. As you do your research, know what citation information you need to record, and keep a permanent record of it. For specific citation styles for different kinds of web sites, see the various citation guides later in this section (MLA, APA, Chicago, and CBE).

A final word on citations: use your judgment. Remember that while the web makes it easy to tap into cutting-edge scholarship on any topic, it also makes it easy to wade a morass of weird, non-academic things posted online. Remember that when you’re writing a scholarly paper, part of your job is to exercise sound judgment about what to cite and what to steer clear of.